1902 Encyclopedia > Ludwig Van Beethoven

Ludwig Van Beethoven

German composer

(1770-1827)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN is in music what Shakespeare is in poetry, a name before the greatness of which all other names, however great, seem to dwindle. He stands at the end of an epoch in musical history, marking its climax, but his works at the same time have ushered in a new phase of progress, from which everything that is great in modern music has taken its rise. This historic side of his genius will have to be further dealt with when the progress of musical art is traced in its continuity. (See article MUSIC, historic section.) At present we have to consider Beethoven chiefly as a man and an individual artist, showing at the same time the reciprocal relations between his life and his work. For although the most ideal artist in that most ideal of arts -- music -- he is always inspired by the deepest sense of truth and reality. The grand note of sadness resounding in his compositions is the reverberation of personal suffering. He was a great artist only because he was a great man, and a sad man withal.

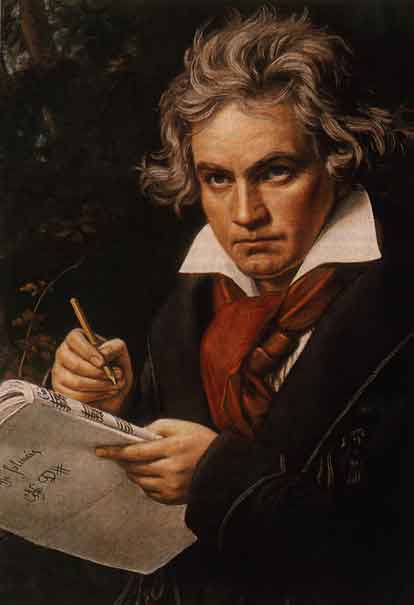

Beethoven at the age of 49, shown working on the score of Missa Solemnis.

At this time Beethoven was already completely deaf.

The family of Beethoven is traceable to a village near Lowen in Belgium, in the 17th century. In 1650 a member of this family, a lineal ancestor of our composer, settled in Antwer. Beethoven’s grandfather, Louis owing to a quarrel with his family, left Belgium for Germany, and came to Bonn in 1732, where his musical talents and his beautiful voice did not long remain unnoticed. The archbishop of Cologne, an art-loving prelate, received him among his court-musicians; the same position afterwards was held by Ludwig’s son, Johann, our composer’s father. The latter was married to Maria Magdalena Keverich, daughter of a cook, and widow of a valet-de-chambre of the elector of Trèves.

The day of our composer’s birth is uncertain; he was baptized Dec. 17, 1770, and received the name of his paternal grandfather Louis, or, in its Germanized form, Ludwig. Beethoven himself seems to have considered the 16th December of the said year his birthday, but documentary evidence is wanting. At one period of his life he believed himself to have been born in 1772, being most likely deceived on the point by his father, who tried to endow his son and pupil with the prestige of miraculous precocity. No less uncertain than the date is the exact place of the great composer’s birth; two houses in Bonn claim the honour of having been the scene of the important event.

The youth of Beethoven was passed under by no means happy circumstances. His father was of a rough and violent temper, not improved by his passion for intoxicating drink, not by the dire poverty under which the family laboured. His chief desire was to reap the earliest possible advantage from the musical abilities of his son, who, in consequence, had at the age of five submit to a severe training on the violin under the father’s supervision. Little benefit was derived from this unsystematic mode of instruction, which, fortunately, was soon abandoned for a more methodical course of pianoforte lessons under a musician of the name of Pfeiffer. Under him and two other masters, Van der Eden and Neefe, Beethoven made rapid progress as a player of the organ and pianoforte; his proficiency in the theoretical knowledge of his art the aspiring composer soon displayed in a set of Variations on a March published in 1783, with the inscription on the title-page, "par un jeune amateur, Louis van Beethoven, age dix ans," a statement the inaccuracy of which the reader will be able to trace to its proper source.

In 1785 Beethoven was appointed assistant of the court-organist Neefe; and in a catalogue raisonné of the musicians attached to the court of the archbishop, he is described as "of good capacity, young, of good, quiet behavior, and poor." The elector of Cologne at the time was Max Franz, a brother of the Emperor Joseph, who seems to have recognized the first sparks of genius in the quiet and little communicative youth. By him Beethoven was, in 1787, sent for a short time to Vienna, to receive a few lessons from Mozart, who is said to have predicted a great future for his youthful pupil.

Beethoven soon returned to Bonn, where he remained for the next five years in the position already described. Little remains to be said of this period of apprenticeship. Beethoven conscientiously studied his art, and reluctantly saw himself compelled to alleviate the difficulties of his family by giving lessons. This aversion to making his art useful to himself by imparting it to others remained a characteristic feature of our master during all his life.

Of the compositions belonging to this time nothing now remains; and it must be confessed that, compared with those of other masters, of Mozart or Handel, for instance, Beethoven’s early were little fertile with regard either to the quantity or the quality of the works produced.

Amongst the names connected with his stay at Bonn we mention only that of his first friend and protector, Count Waldstein, to whom it is said Beethoven owed his appointment at the electoral court, and his first journey to Vienna.

To the latter city the young musician repaired a second time in 1792, in order to complete his studies under Haydn, the greatest master then living, who had become acquainted with Beethoven’s talent as a pianist and composer on a previous occasion. The relation of these two great men was not to be fruitful or pleasant to either of them. The mild, easy-going nature of the senescent Viennese master was little adapted to inspire with awe, or even with sympathy, the fiery Rhenish youth, Beethoven in after life asserted that he had never learned anything from Haydn, and seems even to have doubted the latter’s intention of teaching him in a proper manner.

He seems to have had more confidence in the instruction of Albrechtsberger, a dry but thorough scholar. He, however, and all the other masters of Beethoven agree in the statement, that being taught was not much to the liking of their self-willed pupil. He preferred acquiring by his own toilsome experience what it would have been easier to accept on the authority of others. This autodidactic vein, inherent, it seems, in all artistic genius, was of immense importance in the development of Beethoven’s ideas and mode of expression.

In the meantime his worldly prospect seemed to be of the brightest kind. The introductions from the archbishop and Count Waldstein gave him admittance to the drawing-rooms of the Austrian aristocracy, an aristocracy unrivalled by that of any other country in its appreciation of artistic and especially musical talent. Vienna, moreover, had been recently the scene of Mozart’s triumphs; and that prophet’s cloak now seemed to rest on the shoulders of the young Rhenish musician. It was chiefly his original style as a pianist, combined with an astonishing gift of improvisation, that at first impressed the amateurs of the capital; and it seems, indeed, that even Haydn expected greater things from the executive than from the creative talent of his pupil.

It may be added here, that, according to the unanimous verdict of competent witnesses, Beethoven’s greatness as a pianoforte player consisted more in the bold, impulsive rendering of his poetical intention than in the absolute finish of his technique, which, particularly in his later years, when his growing deafness debarred him from self-criticism, was somewhat deficient.

As a composer Beethoven appeared before the public of the Austrian capital in 1795. in that year his Three trios for Pianoforte and Strings were published. Beethoven called this work his Opus 1, and thus seems to disown his former compositions as juvenile attempts unworthy of remembrance. He was at that time twenty-five, an age at which Mozart had reaped some of the ripest fruits of his genius. But Beethoven’s works are not like those of the earlier master, the result of juvenile and all but unconscious spontaneity; they are the bitter fruits of thought and sorrow, the results of a passionate but conscious strife for ideal aims.

Before considering these works in their chief features, we will add a few remarks as to the life and character of their author. The events of his outward career are so few and of so simple a kind that a continuous narrative seems hardly required. The numerous admirers whom Beethoven’s art had found amongst the highest circles of Vienna, -- Archduke Rudolf, his devoted pupil and friend, amongst the number, -- determined him to take up his permanent residence in that city, which henceforth he left only for occasional excursions to Baden, Modling, and other places in the beautiful surroundings of the Austrian capital. It was here, in his lonely walks, that the master received new impulse from his admiring intercourse with nature, and that most of his grandest works were conceived and partly sketched.

Except for a single artistic tour to Northern Germany in 1796, Beethoven never left Vienna for any length of time. A long-projected journey to England, in answer to an invitation of the London Philharmonic Society, was ultimately made impossible by ill-health.

Beethoven’s reputation as a composer soon became established beyond the limits of his own country, notwithstanding the charges of abstruseness, unpopularity , and the like, which he, like most men of original power, had to submit to from the obtuse arrogance of contemporary criticism.

The summit of his fame, so far as it manifested itself in personal honours conferred upon him, was reached in 1815, when Beethoven celebrated by a Symphony the victories of the Allies over the French oppressor, and was rewarded by the applause of the sovereigns of Europe, assembled at the Congress of Vienna. In the same year he received the freedom of that city, an honour much valued by him.

After that time his immediate popularity began to some extent to decline before the ephemeral splendour of the composers of the day; and the great master seemed henceforth to speak more to coming generations than to his ungrateful contemporaries.

When, however, on rare occasions he emerged form his solitude, the old spell of his overpowering genius proved to be unbroken. In particular, mention must be made of that memorable Academie (concert) in 1824, at which his 9th Symphony, and parts of the grand Missa Solemnis, were performed, producing a storm of applause -- inaudible, alas! to the composer, who had to be turned round by one of the singers to realize, from the waving of hats and handkerchiefs, the effect of his work on the excited multitude.

The last-mentioned incident leads us to one of the most tragic features of Beethoven’s life. By the bitter irony of fate, he who had given to thousands enjoyment and elevation of the heart by the art of sound, was himself deprived of the sense of hearing. The first traces of beginning deafness showed themselves early as 1797, and were perceived by the master with an anxiety bordering on despair. Physicians and quacks were consulted with eagerness, but all their efforts (partly impaired, it must be confessed, by the unruly disposition of the patient) proved unable to stem the encroaching evil. The Royal Library of Berlin possesses a melancholy collection of ear-trumpets and similar instruments, partly made expressly for Beethoven to assist his weakened sense, but all to no avail. In his latter years conversation with him could be carried on by writing only, and of the charms of his own art he was wholly deprived.

But here, again, the victory of mind over matter, -- of genius over circumstance, -- was evinced in the most triumphant manner. It has been asserted, not without reason, that the euphonious beauty of some of Beethoven’s vocal compositions has suffered through his inability to listen to them; but how grand is, on the other hand, the spectacle of an artist deprived of all intercourse with what to him in this world was dearest, and yet pouring forth the lonely aspirations of his soul in works all the more sublime as we seem to hear in them the voice of the innermost spirit of mankind, inaudible to the keen ears of other mortals.

If in this manner the isolation of Beethoven further sublimated his efforts as an artist, it, on the other hand, poignantly intensified his sufferings as a man. His was a heart open to the impressions of friendship and love, and, in spite of occasional roughness of utterance, yearning for the responsive affection of his kind. It is deeply touching to read the following words in the master’s last will, written during a severe illness in 1802:-- "Ye men," Beethoven writes, "who believe or say that I am inimical, rough, or misanthropical, how unjust are you to me in your ignorance of the secret cause of what appears to you in that light… Born with a fiery, lively temper, and susceptible to the enjoyment of society, I have been compelled early to isolate myself and lead a lonely life; whenever I tried to overcome this isolation, oh! how doubly bitter was then the sad experience of my bad hearing, which repelled me again, and yet it impossible for me to tell people, ‘Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.’"

Domestic troubles and discomforts contributed in a minor degree to darken the shadow cast over our master’s life by the misfortune just alluded to. Although by no means insensible to female beauty, and indeed frequently enraptured in his grand, chaste way with the charms of some lady, Beethoven never married, and was, in consequence, deprived of that feeling of home and comfort which only the inceasing care of refined womanhood can bestow.

His helplessness and ignorance of worldly matters completely exposed him to the ill-treatment of servants, frequently, perhaps, excited by his own morbid suspicious and complaints. On one occasion the great master was discovered with his face bleeding from the scratches inflicted by his own valet. It was from amidst such surroundings that Beethoven ascended to the sublime elevation of such works as his Missa Solemnis or his 9th Symphony.

But his deepest wounds were to be inflicted by dearer and nearer hands than those of brutal domestics. Beethoven had a nephew, rescued by him from vice and misery, and loved with a more than father’s affection. His education the master watched with unceasing care. For him he hoarded with anxious parsimony the scanty earnings of his artistic labour. Unfortunately, the young man was unworthy of such love, and at last disgraced his great name by an attempt at suicide, to the deepest grief of his noble guardian and benefactor.

Beethoven died on March 27, 1827, during a terrible thunderstorm. It ought to fill every Englishman’s heart with pride that it was given to the London Philharmonic Society to relieve the anxieties of Beethoven’s deathbed by a liberal gift, and that almost the last utterances of the dying man were words of thanks to his friends and admirers in this country.

Beethoven’s compositions, 138 in number, comprise all the forms of vocal and instrumental music, from the sonata to the symphony, -- from the simple song to the opera and oratorio. In each of these forms he displayed the depth of his feeling, the power of his genius; in some of them he reached a greatness never approached by his predecessors or followers. His pianoforte sonatas have brought the technical resources of that instrument to a perfection previously unknown, but they at the same time embody an infinite variety and depth of emotion. His nine symohonies show a continuous climax of development, ascending from the simpler forms of Haydn and Mozart to the colossal dimensions of the Choral Symphony, which almost seems to surpass the possibilities of artistic expansion, and the subject of which is humanity itself with its sufferings and ideals. His dramatic works-the opera Fidelio, and the overtures to Egmont and Coriolanus -- display depth of pathos and force of dramatic characterization. Even his smallest songs and pianoforte-pieces reflect a heart full of love, and a mind bent on thoughts of eternal things.

Beethoven’s career as a composer is generally divided into three periods of gradual progress. We subjoin a list of his most important compositions, grouped according to the principle indicated.

The first period extends to the year 1800. at the beginning we see Beethoven under the influence of his great predecessors, Haydn and Mozart, but progressing in rapid strides towards independence of thought and artistic power. To this time belong Three trios for Pianoforte and Strings, Op. 1; Sonata for Pianoforte in E flat, Op. 7; Trio for Pianoforte and Strings in B flat, Op. 11; Sonate Pathétique; First Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in C, Op. 15; Adelaida (composed 1797); also the celebrated Septuor, Op. 20 and the First Symphony, Op. 21 (the last two works published in 1800).

The second period, from 1800-1814, marks the climax of formal perfection. The works of this time show the highest efforts of which music as an independent art is capable. We mention the Mass in C, Op. 86; our master’s only opera, Fidelio, and his overture and incidental music to Goethe’s Egmont; the Symphonies, Nos. 2-8, amongst which those called the Pastoral, the Eroica, (FOOTNOTE 506-1) and those in C minor and A major deserve special mention; Concerto for the Violin, Op. 61; Concerti for the Pianoforte, Nos. 3-5; Overtures to Prometheus, Coriolanus, Fidelio, and King Stephen; also numerous sonatas for the pianoforte, quartets, quintets, and other pieces of chamber music.

The third period may be described as that of poetic music, -- a distinct poetic idea becoming the moving principle before which the forms of absolute music have to yield. Beethoven has, by the works belonging to this class, ushered in a new phase of music, as will be further shown in the historical sketch of the art. We name that mequalled master-piece of symphonic art, the Ninth or Choral Symphony; the Missa Solemnis; the Sonatas for Pianoforte, numbered respectively Op. 101, 102, 106, 109, 110, 111; the marvellous Quartets for Strings, Op. 127, 130, 132, 135; also the 33 Variations on a Valse by Diabelli, Op. 120.

For fuller information on the great master’s life and works than our limited space has permitted us to give, we refer the reader to the biographical and critical works of Schindler, Thayer, Mohl, Marx, and Nottebohm. (F. H.)

Footnote

(506-1) This symphony was originally written in celebration of Napoleonm at that time consul of the French Republic. When Beethoven heard of his assuming the imperial title, he tore off the dedication and trampled it under foot.

The above article was written by Francis Hueffer, Ph.D., formerly musical critic of The Times; author of The Troubadours: a History of Provençal Life and Literature in the Middle Ages and Richard Wagner and the Music of the Future; editor of Great Musicians.

|