1902 Encyclopedia > George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel

(Georg Friedrich Händel)

German-English composer

(1685-1759)

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL (1685-1759), one of the greatest names in the history of music generally, is absolutely paramount in that of English music. His influence on the artistic development of England and his popularity, using that word in the most comprehensive sense, are perhaps unequalled. He has entered into the private and the political life as well as into the art life of Englishmen; without him they cannot bury their dead or elect their legislators; and never has a composer been more essentially national than the German Handel has become in England. It may on the other hand be said that but for his sojourn in that country Handel would never have been what he was. It was under the influence of English poetry, and of English national and religious life, that his artistic conception broadened and gained the dignity and grandeur which we see in his oratorios, and which was wanting, and , seeing the style of art, could not but be wanting, in his Italian operas.

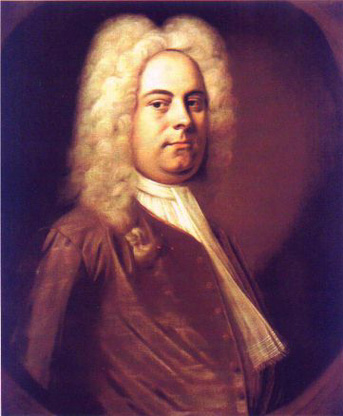

Handel in 1727

(painting by Balthasar Denner)

The day of Handel’s arrival in London, late in the autumn of 1710, was indeed an eventful day in the life of Handel as well as in the annals of English music, and the facts of his biography preceding that date may be summed up with comparative brevity.

George Frederick Handel (in German the name in always Händel) was born at Halle in Saxony on February 23, 1685, the same year which gave birth to his great fellow composer Johann Sebastian Bach (Footnote 434-1). He was the son of George Handel, who according to the custom of the time combined the occupations of barber and surgeon, and subsequently rose to be valet-de-chambre to the elector of Saxony. His second wife, Dorothea Taust, was the daughter of a clergyman, and to her the great composer remained attached with all the ties of filial affection.

His father was sixty-three years old when Handel was born, and the musical talent shown by the youth at a very early age found little encouragement from the stern old gentleman, who looked upon art with contempt, and destined his son for the law.

Many are the anecdotes relating to the surreptitious way in which the youth practiced the forbidden art on a little spinet smuggled into his attic by the aid of a good-natured aunt, and fortunately of too feeble tone to be audible in the lower part of the house. at the age of eight the boy accompanied his father on a visit to Saxe Weissenfels, and it was there that the proficiency acquired in the manner above described was turned to excellent account; for, having made acquaintance with the court musician and being allowed to practice on the organ, he was on occasion overheard by the duke himself, who immediately recognizing his talent spoke seriously to the father on his behalf.

To such a remonstrance coming from such a quarter the valet-de-chambre had of course to submit, and henceforth Handel was allowed to practice his art, and after his return to Halle even received musical instruction from Zachau, one of the best organists of the town. It was under his somewhat mechanical but thorough tuition that Handel acquired his knowledge of counterpoint; he also soon became an excellent performer on the organ.

His first attempts at composition date from an equally early period, and in his twelfth year he made his debut as a virtuoso at the court of Berlin with such success that the elector of Brandenburg, afterwards King Frederick I. of Prussia, offered to send him to Italy, a proposal declined by Handel’s father for unknown reasons.

In 1697 the latter died, and the young artist was henceforth thrown on his own resources. For some years he remained in Halle, where in 1702 he obtained a position as organist; but in the following year we find him at Hamburg, at that time one of the musical centres of Germany. There the only German opera worth the name had been founded by Reinhold Keiser, the author of innumerable operas and operattas, and was flourishing at the time under his direction. Handel entered the orchestra, and soon rose from his place amongst the second violins to the conductor’s seat at the clavicenbalo, which he occupied during Keiser’s absence, necessitated by debt.

It was at Hamburg that he became acquainted with Mattheson, a fertile composer and writer on musical subjects, whose Volkommener Kapellmeister (1739) and Ehrenpforte (1740) are valuable sources for the history of music. The friendship of the two young men was not without some curious incidents. On one occasion they set out together on a journey to Lubeck, where the place of organist at one of the churches was vacant. Arrived at Lubeck, they discovered that on of the conditions for obtaining the place was the hand of the elderly daughter of the former organist, the celebrated Buxtehude, whereat the two candidates forthwith returned to Hamburg.

Another adventure might have had still more serious consequences. At a performance of Mattheson’s opera Cleopatra at Hamburg, Handel refused to give up the conductor’s seat to the composer, who was also a singer, and was occupied on the stage during the early part of his work. The dispute led to an improvised duel outside the theatre, and but for a large button on Handel’s coat which intercepted his adversary’s sword, there would have been no Messiah or Israel in Egypt.

In spite of all this the young men remained friends, and Mattheson’s writings are full of the most valuable facts for Handel’s biography. He relates in his Ehrenpforte amongst other things that his friend at that time used to compose "interminable cantatas" of no great merit, but of these no trace now remains, unless we assume that a "Passion" according to St John (German words by Poste), the MS. of which is at the Royal Library, Berlin, is amongst the works alluded to. It was composed in 1704.

The year after this witnessed Handel’s first dramatic attempt -- a German opera, Almira, performed at Hamburg on January 8, 1705, with great success, and followed a few weeks later by another work of the same class, Nero by name.

In 1706 he left Hamburg for Italy, At that time still the great school of music, to which indeed Handel himself owed his skill and experience in writing for the voice. He remained in Italy for three years, living at various times in Florence, Rome, Naples, and Venice. He is said to have made the acquaintance of Lotti, of Alessandro Scarlatti, and of the latter’s son Domenico, the father of modern pianoforte playing. His compositions during his Italian period were two operas, two oratorios, Resurrezione and Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, afterwards developed into the English oratorio the Triumph of Time and Truth, and numerous other choral works.

It was during these years that the composer’s earliest or Italian style reached its full maturity, and that his name became widely known in the musical world. In the chief cities of Italy "il Sassone," as Handel, like his countryman Hasse twenty years later, was nicknamed, was received with every mark of favor and esteem.

But his own country also began to acknowledge his merits. At Venice in 1709 Handel received the offer of the post of capellmeister to the elector of Hanover, transmitted to him by his patron and staunch friend of later years Baron Keilmansegge.

The composer at the time contemplated a visit to England, and he accepted the offer only on condition of leave of absence being granted to him for that purpose. To England accordingly Handel journeyed after a short stay at Hanover, arriving in London towards the close of 1710. curiously enough he came as a composer of Italian opera, and in that capacity he earned his first success at the Haymarket with the opera Rinaldo, composed it is said in a fortnight, and first performed on February 24, 1711. The beautiful and still universally popular air "Lascia ch’io pianga" is from this opera. A similar air in the form of a sarabande occurs in Almira.

After the close of the season in June of the same year Handel seems to have returned to Germany for a short time; but the temptation of English fame or English gold proved too powerful, and in January 1712 we find him back in London, evidently little inclined to return to Hanover in spite of his duties at the court there.

Two Italian operas, the celebrated Utrecht Te Deum written by command of Queen Anne, and other works belong to this period. It was in such circumstances somewhat awkward for the composer when his deserted master came to London as George I. of England. Neither was the king slow in resenting the wrongs of the elector. For a considerable time Handel was not allowed to appear at court, and it was only through the intercession of his patron Baron Kielmansegge that his pardon was at last obtained.

Commissioned by the latter, Handel wrote his celebrated Water Music, which was performed at a great fete on the Thames, and so pleased the king that he at once received the composer to his good graces. A salary of £200 a year granted to Handel was the immediate result of this happy consummation. In 1716 he followed the king to Germany, where he wrote a second German "Passion," the words this time being supplied by Brockes, a well-known poet of the day. after his return to England he entered the service of the duke of Chandos as conductor of his private concerts.

In this capacity he resided for three years at Cannons, the duke’s splendid seat near Edgeware, and produced the two Te Deums and the twelve Anthems surnamed Chandos. The English pastoral Acis and Galatea (not to be mistaken for the Italian cantata of that name written at Naples, with which it has nothing in common), and his first oratorio to English words Esther, were written during his stay at Cannons.

It was not till 1720 that he appeared again in a public capacity, viz., in that of impresario of an Italian opera at the Haymarket Theatre, which he managed for the so-called Royal Academy of Music. Senesino, a celebrated singer, to engage whom he composer specially journeyed to Dresden, was the mainstay of the enterprise, which opened with a highly successful performance of Handel’s opera Radamista. Muzio Scevola, written in conjunction with Buononcini and Ariosti, Tamerlane, Rodelinda, and other operas composed for the same theatre, are now forgotten, only detached songs being heard at concerts.

To this time also belongs the celebrated rivalry of Handel and Buononcini, a gifted Italian composer, who by his clique was declared to be infinitely superior to the German master. The controversy raised a storm in the aristocratic teapot, and has been perpetuated in the lines generally but erroneously attributed to Swift, and in reality written by John Byron:--

Some say, compared to Buononcini,

That Mynheer Handel’s but a ninny;

Others aver that he to Handel

Is scarcely fit to hold a candle

Strange all this difference should be

‘Twixt Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee.

Although the contempt for music, worthy of Chesterfield himself, shown in these lines may seem absurd, they yet contain a grain of truth. Handel differed from his rival only in degree not in essence. In other words, he was an infinitely greater composer than Buononcini, but had he continued to write Italian opera there is no reason to conclude from his existing works of that class that he would have reformed or in any essential point modified the existing genre. The contest was therefore essentially of a personal nature, and in these circumstances it is hardly necessary to add that Handel remained victorious. Buononcino for a reason not sufficiently explained left London, and Handel was left without a rival.

But in spite of this his connection with Italian opera was not to be a source of pleasure or of wealth to the great composer. For twenty years the indomitable master was engaged in various operatic ventures, in spite of a rival company under the great singer Farinelli, started by his enemies, -- in spite also of his bankruptcy in 1737 and an attack of paralysis caused by anxiety and overwork. Of the numerous operas produced by him during this period it would be needless to speak in detail. Only the name of the final work of the long series, Deidamia, produced in 1741, may be mentioned here.

That Handel’s non-success was not caused by the inferiority of his works to those of other composers is sufficiently proved by the fact that the rival company also had to be dissolved for want of support.

But Handel was in more than one way disqualified for the post of operatic manager, dependent in those days even more than in ours on the patronage of the great. To submit to the whims and the pride of the aristocracy was not in the nature of the upright German, who even at the concerts of the princess of Wales would use language not often heard at courts when the talking of the ladies during the performance irritated him.

And, what was perhaps still more fatal, he opposed with equal firmness the caprices and inartistic tendencies of those absolute rulers of the Italian stage -- the singers. The story is told that he took hold of obstinate prima donna and held her at arm’s length out of window, threatening to drop her into the street below unless she would sing a particular passage in the proper way.

Such arguments were irresistible at the time, but their final results were equally obvious, in spite of Handel’s essentially kindly nature and the ready assistance he gave to those who really wished to learn. No wonder therefore that his quarrels with virtuosi were numerous, and that Senesino deserted him at a critical moment for the enemy’s camp.

It is a question whether Handel’s change from opera to oratorio has been altogether in the interest of musical art. The opera lost in him a great power, but it may well be doubted whether dramatic music such as it was in those days would have been a proper mould for his genius. Neither is it certain that genius was, strictly speaking, of a dramatic cast. There are no doubts in his oratorios -- for in these alone Handel’s power is displayed in its maturity -- examples of great dramatic force of expression; but Handel’s genius was in want of greater expansion than the economy of the drama will allow of.

It was no doubt for this reason that from an inner necessity he created for himself the form of the oratorio, which in spite of the dialogue in which the plot is developed is in all essentials the musical equivalent of the epic.

This breadth and depth of the epic is recognized in those marvelous choral pieces expressive either of pictorial detail (as the gnats and the darkness tangible and impenetrable in Israel in Egypt) or of the combined religious feeling of an entire nation. By the side of these even the finest solo pieces of Handel’s scores appear comparatively insignificant, and we cannot sufficiently wonder at the obtuseness of the public which demanded the insertion of miscellaneous operatic arias as a relief from the incessant choruses in Israel in Egypt at the second performance of that great work in 1740.

Handel is less the exponent of individual passion than the interpreter of the sufferings and aspirations of a nation, or in a wider sense of mankind. Take, for instance, the celebrated Dead March in Saul. It is full of intense grief, in spite of the key of C major, which ought once for all to dispel the prejudice that sorrow always speaks in minor keys. Even Chopin himself has not been able to give utterance to the feeling in more impressive strains. And yet the measured and decisive rhythm, and the simple diatonic harmonies, plainly indicate that here a mighty nation deplores the death of a hero.

It is for the same reason that Handel’s stay in England was of such great influence on his artistic career. Generally speaking, there is little connection between politics and art. But it may be said without exaggeration that only amongst a free people, and a people having a national life such as England alone had in the last century, such national epics as Judas Maccabaeus and Israel in Egypt could have been engendered. In the same sense the Messiah became the embodiment of the deep religious feeling pervading the English people, and Handel, by leaving Italian opera for the oratorio, was changed from the entertainer of a caste to the artist of the people in the highest and widest sense. The Messiah is indeed the musical equivalent of Milton’s Paradise Lost.

This leads us to another and equally important aspect of the same subject -- the important influence of English poetry on Handel’s works. Not only are some of the greatest names of English literature -- Milton (Allegro and Penseroso), Dryden (Alexander’s Feast), Pope (St Cecilia’s Ode) -- immediately connected with Handel’s compositions, but the spirit of these poets, and especially of Milton, pervades his oratorios even when he has to deal with the atrocious doggerel of Morell or Humphreys.

In addition to this Handel received many a valuable suggestion from the works of Purcell and other early English musicians with which he was acquainted.

No wonder therefore that Englishmen claim Handel as one of themselves, and have granted him honours both during his lifetime and after his death such as have fallen to the share of few artists. But in spite of all this it is impossible to deny that the chances of a national development of English music were, if not absolutely crushed, at least delayed for centuries by Handel.

Under Elizabeth and James England had a school of music which, after the storms of the civil war, was once more revived by such masters as Pelham Humphrey and his great pupil Purcell. The latter, although cut off in his youth, had left sufficient seed for a truly national growth of English music.

But Handel soon concentrated the interest of connoisseurs and people on his own work, and native talent had to abandon the larger sphere of the metropolis for the comparative seclusion of the cathedral.

The following is a chronological list of Handel’s English oratorios taken from the catalogue of his works appended to Mr. J. Marshall’s article in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. i. p. 657. Esther (1720), Deborah 1733), Athalia (1733), Saul (1738), Israel in Egypt (1738), Messiah (1741), Samson (1741), Joseph (1743), Hercules (1744, Belshazzar (1744), Occasional (1746), Judas Maccabaeus (1746), Alexander Balas (1747), Joshua (1747), Solomon (1748), Susanna (1748), Theodora (1749), Jephtha (1751), Triumph of Time and Truth (1757).

The sequence of these dates will show that the transition from Italian opera to sacred music was very gradual, and caused by circumstances rather than by premeditated choice.

It would lead us too far to enter here into the genesis of each of these works, but a few remarks must be added with regard to Handel’s summum opus the Messiah. It was written in twenty-four days and first performed April 18, 1742, at Dublin, where Handel was staying on a visit to the duke of Devonshire, lord-lieutenant of Ireland.

Its first performance in London took place on March 23rd of the following year. Its introduction into Handel’s native country was due to Philip Emanuel Bach, the son of the great Bach, who conducted it at Hamburg. At Berlin it was for the first time given in April 1786, under the leadership of Adam Hiller, who also introduced it a few months later at Leipsic [Leipzig] against the advice of all the musicians of Saxony. At the Berlin performance Signora Carrara, the celebrated singer, inserted in the first part an aria by Traetta, in which, according to a contemporary account, "she took much trouble to please the public, and the bravura passages of which she delivered with great success."

Two years before this had taken place the great Handel commemoration at Westminster Abbey, when on the third day of the festival, May 29, 1784, the Messiah was splendidly performed by an orchestra and chorus of 525 performers. In the appreciation of Handel England thus was far in advance of Germany.

The remainder of Handel’s life may told in few words. Owing to the machinations of his enemies he for a second time became a bankrupt in 1745, but nothing, not even his blindness during the last six years of his life, could daunt his energy.

He worked till the last, and attended a performance of his Messiah a week before his death, which took place on April 14, 1759. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. His monument is by Roubilliac, the same sculptor who modeled the statue erected during Handel’s lifetime in Vauxhall Gardens.

Handel was a man of character and high intelligence, and his interest was not, like that of too many musicians, confined to his own art exclusively. He liked the society of politicians and literary men, and he was also a collector of pictures and articles of vertu. His power of work was enormous, and the list of his works would fill many pages. They belong to all branches of music, from the simple air to the opera and oratorio.

His most important works of the two last-named classes have already been mentioned. But his instrumental compositions, especially his concerti for the organ his suites de pièces for the harpsichord, ought not to be forgotten. Amongst the contrapuntists of his time Handel had but one equal -- Bach. But he also was a master of the orchestra, and, what is more, possessed the inate gift of genuine melody, unfortunately too often impeded by the rococo embellishments of his arias.

The extraordinary rapidity with which he worked has been already referred to. It is true that when his own ideas failed him he helped himself to those of others without the slightest compunction. The system of wholesale plagiarism carried on by him is perhaps unprecedented in the history of music. He pilfered not only single melodies, but frequently entire movements from the works of other masters, with few or no alterations and without a word of acknowledgement.

A splendid collection of Handel’s MSS., six volumes in all, is in the possession of her Majesty at Buckingham Palace. The Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge also possesses seven volumes, mostly sketches and notes for greater works, in the composer’s handwriting. The German and English Handel Societies (the latter founded in 1843 and dissolved in 1848) have issued critical editions of his more important works. Three biographers of Handel deserve mention – an Englishman, Mainwaring, Memoirs of the Life of the late G. F. Handel (1760), a Frenchman, M. Victor Schoelcher, and a German, Herr Chrysander. ( F. H.)

Footnote

(434-1) The date, 23rd February 1684, given on his tombstone in Westminster Abbey is incorrect.

The above article was written by Francis Hueffer, Ph.D., formerly musical critic of The Times; author of The Troubadours: a History of Provençal Life and Literature in the Middle Ages and Richard Wagner and the Music of the Future; editor of Great Musicians.

|