1902 Encyclopedia > Mural Decoration > Subjects of Mediaeval Mural Paintings. Method of Execution.

Mural Decoration

(Part 16)

PAINTING AND MURAL DECORATION (cont.)

Subjects of Mediaeval Mural Paintings. Method of Execution.

Subject of Mediaeval Wall-Paintings.— In churches and domestic buildings alike the usual subjects represented on the walls were specially selected for their moral and religious teaching, either stories from the Bible an Apocrypha, or from the lives of saints, or lastly, symbolicall representations setting forth some important theological truth, such as figures of Virtues and Vices, or the Scala Humanae Salvationis, showing the perils and temptations of the human soul in its struggle to escape hell and gain paradise—a rude foreshadowing of the great scheme worked out with such perfection by Dante in his Commedia. A fine example of this subject exists on the walls of Chaldom Church, Surrey.[Footnote 46-1] In selection of saints for paintings in England, those of English origin are naturally most frequently represented, and different districts had certain local favourites. St Thomas of Canterbury was one of the most widely popular; but few examples now remain, owing to Henry VIII.’s special dislike to this saint and the strict orders that were issued for all pictures of him to be destroyed. For a similar reason most paintings of saintly were obliterated.

Method of Execution.— Though Eraclius, who probably wrote before the 10th century, mentions the use of an oil-medium, yet till about the 13th century mural paintings appear to have been executed in the most simple way, in tempera mainly with earth colours applied on dry stucco ; even when a smooth stone surface was to be painted a thin coat of whitening or fine gesso was laid as a ground. No instance of true fresco has been discovered in England. In the 13th century, and perhaps earlier oil was commonly used both as a medium for the pigments and also to make a varnish to cover and fix tempera paintings. Vasari’s statement as to the discovery of the use of oil-medium by the Van Eycks is certainly untrue, but it probably has a germ of truth. The Van Eycks introduced the use of dryers of a better kind than had yet been used, and so largely extended the application of oil-painting. Before their time it seems to have been the custom to dry wall-paintings laboriously by the use of charcoal braziers, if they were in a position where the sun could not shine upon them. This is specially recorded in the valuable series of account for the expenses of wall-paintings in the royal palace of Westminster during the reign of Henry III., printed in Vetusta Monumenta, vol. vi., 1842. All the materials used, including charcoal to dry the painting and the wages paid to the artists, are given. The materials mentioned are plumbum album et rubeum, viridus, vermilio, synople, ocre, azura, aurum, argentum, collis oleum, vernix.

Two foreign painters were employed—Peter of Spain and William of Florence—at sixpense a day, but the English painters seem to have done most of the work and received higher pay. William, an English monk in the adjoining Benedictine abbey of West-minster, received two shillings a day. Walter of Durham and various members of the Otho family, royal goldsmiths and moneyers, worked for many years on the adornment of Henry III.’s palace and were well paid for their skill. Some fragments of paintings from the royal chapel of St Stephen are now in the British Museum. They are very delicate and carefully-painted subjects from the Old Testament, in rich colours, each with explanatory inscription underneath. The scale is small, the figures being scarcely a foot high. Their method of execution is curious. First the smooth stone wall with a coat of red, painted in oil, probably to keep back the damp; on that a thin skin of fine gesso (stucco) has been applied, and the outlines of the figures marked with a point; the whole of the background, crowns, borders of dresses, and other ornamental parts have then been modelled and stamped with very minute patterns in slight relief, impressed on the surface of the gesso while it was yet soft. The figures have then been painted, apparently in tempera, gold leaf has been applied to the stamped reliefs, and the whole has been covered with an oil varnish. It is difficult to realize the amount of patience and labour required to cover large halls such as the above chapel and the "painted chamber," the latter about 83 feet by 27, with this minute and gorgeous style of decoration.

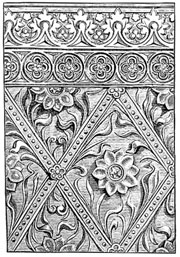

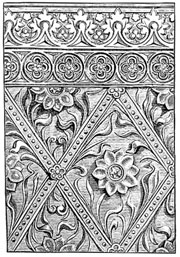

In many cases the grounds were entirely covered with shining metal leaf, over which the paintings were executed; those parts, such as the draperies, where the metallic lustre was wanted, were painted in oil with transparent colours, while the flesh was painted in opaque tempera. The effect of the bright metal shining through the rich colouring is very magnificent. This extreme minuteness of much of the medieval wall-decoration is very remarkable. Large wall-surfaces and intricate mouldings were often completely covered by elaborate gesso patterns in relief of almost microscopic delicacy (fig. 17). The cost of stamps for this is among the items in the Westminster accounts. These patterns when set and dry were further adorned with gold and colours in the most laborious way. So also with the architectural painting; the artist was not content simply to pick out the various members of the mouldings in different colours, but he also frequently covered each bead or fillet with painted flowers and other patterns, as delicate as those in an illuminated MS., --so minute and highly-finished that they are almost invisible at a little distance, but yet add greatly to the general richness of effect. All this is completely neglected in modern reproduction of medieval painting, in which both touch and colour are alike coarse and harsh—mere caricatures of the old work, such as unhappily disfigure the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and many cathedrals in France, Germany, and England. Gold was laid being broken up by some such delicate reliefs as that shown in fig. 17, so its effect was never gaudy or dazzling.

Fig. 17 -- Pattern in Stamped and Moulded Plaster, decorated with gilding and transparent colours; 15th century work. Full size.

Mural painting in England fell into disuse in the 16th century. For domestic purposes wood panelling stamped leather, and tapestry were chiefly used as wall-coverings In the reign of Henry VIII., probably in part through Holbein’s influence, a rather coarse sort of tempera wall painting, German in style appears to have been common. [Footnote 47-1]

A good example of arabesque painting of this period in black and white, rudely though boldly drawn and very Holbeinesque in character, was discovered in 1881 behind the panelling in one of the canon’s houses at Westminster. Other examples exist at Haddon Hall (Derbyshire) and elsewhere.

Several attempts have been made in the present century to revive the art of monumental wall-decoration, but mostly, like those in the new House of Parliament, unsuccessful both in method and design. A large-wall-painting by Sir Frederick Leighton of the Arts of War, on a wall in the South Kensington Museum is much disfigured by the disagreeabl gravelly surface of the stucco. The process employed is that invented by Mr Gambier Parry, and called by him "spirit fresco." A very fine series of mural paintings has been executed by Mr Madox Brown on the walls of the Manchester town-hall. These also are painted in Mr Parry’s "spirit fresco," but on a smooth stucco, free from the unpleasant granular appearance of the South Kensington picture.

Footnote

(46-1) See Collections of Surrey Archaeol. Soc., vol. v. part ii. , 1871. A useful though necessarily incomplete list of English mediaeval mural paintings has been published by the Science and Art Depart., S. Kens. Mus. Fresh wall-paintings are constantly being discovered under later coats of whitewash, so that any list needs frequently additions.

(47-1) Shakespeare, Henry IV., part ii., act 2, sc. 1 : "Falstaff. And for the walls, a pretty slight drollery, or the story of the prodigal, or the German hunting in waterwork, is worth a thousand of these bed-hangings and these fly-bitten tapestries."

Read the rest of this article:

Mural Decoration - Table of Contents

|