1902 Encyclopedia > Emperor Nero

Nero

Roman Emperor

(37-68 AD)

NERO, (37-68 A.D.), Roman emperor, the only child of Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus and the younger Agrippina, was born at Antium on December 15, 37 A.D., nine months after the death of the emperor Tiberius. Though in both his father’s and his mother’s side he came of the blood of Augustus, and the astrologers are said to have predicted that he would one day be emperor, the circumstances of his early life gave little presage of his future eminence. His father Domitius, at best a violent, pleasure-seeking noble, died when Nero was scarcely three years old. In the previous year (39 A.D.) his mother had been banished by order of her brother the emperor Caligula on a charge of treasonable conspiracy, and Nero, thus early deprived of both parents, found a bare shelter in the house of his aunt Domitia, where two slaves, a barber and a dancer, commenced of Caligula in 41 A.D. his prospects improved, for Agrippina was recalled from exile by her uncle, the new emperor Claudius, and resumed the charge of her young son.

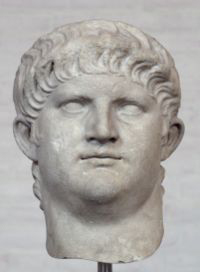

Emperor Nero

(Marble bust in Glyptothek, Munich)

Nero’s history during the next thirteen years is summed up in the determined struggle carried on by his mother to win for him the throne which it had been predicted should be his. The fight was a hard one. Messalina, Claudius’s wide, as all powerful with her husband, and her son Britannicus was by common consent regarded as the next in succession. But on the other hand Claudius was weak and easily led, and Agrippina daringly aspired to supplant Messalina in his affections. To outweigh Britannicus’s claims as the son of the reigning emperor, she relied on the double prestige which attached to her own son, as being at once the grandson of the popular favourite Germanicus and the lineal descendant of Augustus himself. Above all, she may well have put confidence in her own great abilities, indomitable will, and untiring energy, and in her readiness to sacrifice everything, even her personal honour, for the attainment of the end she had in view. Her first decisive success was gained in 48 by the disgrace and execution of Messalina. In 49 followed her own marriage with her uncle Claudius, and her recognition as his consort in the government of the empire.1 She now freely used her ascendency to advance the interests of her son. The Roman populace already looked with favour on the grandson of Germanicus, but in 50 his claims obtained a more formal recognition from Claudius himself, and the young Domitius was adopted by the emperor under the title of Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus.2 Agrippina’s next step was to provide for her son the training needed to fit him for the brilliant future which seemed opening before him. The philosopher L. Annaeus Seneca was recalled from exile and appointed tutor to the young prince. On December 15, 51, Nero completed his fourteenth year, and Agrippina, in view of Claudius’s failing health, determined to delay no longer his adoption of the toga virilis. The occasion was celebrated in a manner which seemed to place Nero’s prospects of succession beyond the reach of doubt. He was introduced imperium senate by Claudius himself. The proconsular imperium and the little of "princeps juventutis" were conferred upon him.3 He was specially admitted as an extraordinary member of the great priestly colleges, and his name was included by the Arval Brethren in their prayers for the safety of the emperor and his house. Largesses and donations delighted the populace and the soldiery, and at the games in the cirsus Nero’s appearance in triumphal dress contrasted significantly with the simple toga praetexta worn by Britannicus. During the next two years Agrippina followed up this great success with her usual energy. Britannicus’s leading partisans were banished or put to death, and the all-important command of the praetorian guard was transferred to Afranius Burrus, formerly a tutor of Nero’s and devoted to his service. Nero himself was put prominently forward whenever occasion offered. The petitions addressed to the senate by the town of Bononia and by the communities of Rhodes and Ilium were gracefully supported by him in Latin and Greek speeches, and during Claudius’s absence in 52 at the Latin festival it was Nero who, as prefect of the city, administered justice in the forum to crowds of suitors. Early in 53 his marriage with Claudius’s daughter, the ill-fated Octavia, drew still closer the ties which connected him with the imperial house, and now nothing but Claudius’s death seemed wanting to secure his final triumph. This event, which could not in the course of nature be long delayed. Agrippina determined to hasted, and the absence, through illness, of the emperor’s trusted freedman Narcissa favoured her schemes. On October 13, 54, Claudius died, poisoned, as all our authorities declare, by the orders of his unscrupulous wife. For some hours the fact of his death was concealed, but at noon the gates of the polars were thrown open, and Nero was presented to the soldiers on guard as their new sovereign. From the steps of the salutations of the troops, and thence to the senate-house, where he was fully and promptly invested with all the honours, titles, and powers of emperor.4

Agrippina’s bold stroke had been completely successful. Its suddenness has disarmed opposition: only a few voices were raised for Britannicus; nor is there any doubt that Rome was prepared to welcome the new emperor with genuine enthusiasm. To his descent from Germanicus and from Augustus he owned a prestige which was strengthened by the general belief in his own good qualities. He was young, generous, and genial. His abilities, really considerable, were skillfully assisted and magnified by Seneca’s ready dexterity, while the existence of his worse qualities- his childish vanity, ungovernable selfishness, and savage temper- was as yet unsuspected y\by all but those immediately about him. His first acts confirmed the favourable impressions thus produced. With graceful modesty he declined the venerable title of "pater patriae." The memory if Claudius, and that of his own father Augustus, and to avoid the errors and abuses which had multiplied under the role at once lax and arbitary of his predecessor, while his unfailing clemency, liberality, and affability were the talk of Rome. Much no doubt of the credit of all this is due to Seneca, and his faithful ally Burrus. Seneca had seen him the first that the real danger with Nero lay in the same vehemence of his passions, and he made it his chief aim to stave off by every means in his power the dreaded outbreak of "the wild beast" element in his pupil’s nature. He indulged him to the full in all his tastes, smoothed away opposition, and, while relieving him as far as possible of the more irksome duties of government, gave him every facility for easily winning the applause he craved for by acts of generosity which cost him little. Nor, is it certain that any other policy would have succeeded better with a nature like, Nero’s which had never known training or restraint, and now reveled with childish delight in the consciousness of absolute power. Provided only that the wild beast did not taste blood, it mattered little if respectable society was scandalized at the sight of an emperor whose chief delight was in pursuits hitherto left to Greek slaves and freedmen. At any rate the policy succeeded for the time. During the first five years of his reign, the golden "quinquennium Neronis," little occurred to damp the hopes excited by his bahaviour on succeeding to the throne. His clemency of temper was unabated. His promises of constitutional moderation were amply fulfilled, and the senate found itself free to discuss and even to decide important administrative questions. Abuses were remedied, the provincials protected from questions. Abuses were remedied, the provincials protected from oppressed, and the burdens of taxation lightened. On the frontiers, thanks chiefly to Corbulo’s energy and skill, no disaster occurred serious enough to shake the general confidence in the government, and even the murder of Britannicus seems to have been easily pardoned at the time as a necessary measure of self defence. But Seneca’s fears of what the consequences would be, should Nero’s sleeping passions once be roused, were fully verified by the result, and he seems to have seen all along from what quarter danger was to be apprehended. Agrippina’s imperious temper and insatiable love of power made it certain that she would now willingly abandon her ascendancy over her son, and it was scarcely less certain that her efforts to retain it would bring her into collision with his ungovernable self-will. At the same time the success of Seneca’s own management of Nero largely depended on his being able gradually to emancipate the emperor form his mother’s control. During the first few months of Nero’s reign the chances of such as emancipation seemed respect, but consulted her on all affairs of state. In 55, however, Seneca found a powerful ally in Nero;s passion for the beautiful freedwoman Acte, a passion which he deliberately encouraged for his own purposes. Agrippina’s injured pride provoked her to angry remonstrances, which served only to irritate her wayward son, and the caresses by which she endeavoured to repair her mistakes equally failed in their object. Furious at her threatened to espouse of the injured Britannicus. But her threats only served to show that her son, if once his will was crossed, or his fears aroused, could be as unscrupulous and head-strong as his mother. Britannieus was poisoned as he sat at table. Agrippina, however, still persisted. She attempted to win over Nero’s neglected wife Octavia, and to form a party of her own within the court. Nero replied by dismissing her guards, and placing herself in a sort of honourable confinement. 1 This second defeat seems to have decided Agrippina to acquesce in her deposition from the leading position she had filled since 49. During nearly three years she disappears from the history, and with her retirement things again for the time went smoothly. In 58, however, fresh cause for anxiety appeared. For the second time Nero was enslaved by the charms of a mistress. But Poppaea Sabina, the new favourite, was a woman of a very different stamp from her predecessor. High-born, wealthy, and accomplished, she had no mind to be merely the emperor’s plaything. She was resolved to be his wife, and with consummate skill she set herself at once to remove the obstacles which stood in her way. Her first object was the final ruin of Agrippina. By taunts and caresses she drove her weal and passionate lover into a frenzy of fear and baulked desire. She taught him easily enough to gate and dislike his mother as an irksome check on his freedom of action, and as dangerous to his personal safety. To get rid of her, no matter how, became his one object, and the diabolical ingenuity of Anicetus, a freedman, and now perfect of the fleet at Misenum, devised a means of doing so without unnecessary scandal. Agrippina was invited to Baiae, and after an affectionate reception by her son was conducted on board a vessel so constructed as, at a given signal, to fall to pieces and precipitate its passengers into the waters of the lake. But the manoeuvre failed. Agrippina saved herself by swimming to the shore, and at once wrote to her son, announcing her escape, and affecting entire ignorance of the plot against her. The news filled Nero with consternation, but once again Anicetus came his rescue. A body of soldiers under his command surrounded Agrippina’s villa, and murdered her in her chamber. 2 The deed done, Nero was for the moment horrorstruck at the enormity of the crime, and terrified at its possible consequences to himself. But a six months’ residence in Campania, and the congratulations which poured in upon him from the neighbouring towns, where the report had been officially spread that Agrippina had fallen a victim to her own treacherous designs upon the emperor’s life, gradually restored his courage. In September 59 he re-entered Rome amid universal rejoicing, fully resolved upon enjoying his dearly bought freedom. A prolonged carnival followed, in which Nero reveled in the public gratification of the tastes which he had hitherto ventured to indulge only in comparative privacy. Chariot races, musical and dramatic exhibitions, games in the Greek fashion, rapidly succeeded each other. In all the emperor was a prominent figure, and the fashionable world of Rome, willingly or unwillingly, followed the imperial example. These revels, however, extravagant as they were, at least involved no bloodshed, and were humanizing and civilized compared with the orthodox Roman gladiatorial shows. A far more serious result of the death of Agrippina was the growing influence over Nero of Poppaea and her friends; and in 62 their influence over Nero of Poppaea and her friends; removal of the trusty advisers who had hitherto stood by the emperor’s side. Burrus died early in that year, it was said from the effects of poison, and his death was immediately followed by the retirement of Seneca from a position which he felt to be no longer tenable. Their place was filled with Nero’s sensual tastes has gained him the command of the praetorian guards in succession to Burrus. The two now set themselves to attain a complete mastery over the emperor. The haunting fear of conspiracy, which had unnerved stronger Caesars before him, was skillfully used Cornelius Sulla, who had been banished to Massilia in 58, was put to death on the ground that his residence in Gaul was likely to arouse disaffection in that province, and a similar charge proved fatal to Ruvellius Plautus, who had for two years been living in retirement in Asia. 3 Nero’s taste for blood thus whetted, a more illustrious victim was next found in the person of the unhappy Octavia. At the instigation of Poppaea she was first divorced and then banished to the island of Pandateria, where a few days later she was barbarously murdered. Poppaea’s triumph was now complete. She was formally married to Nero; her head appeared on the coins side by side by side with his; and her statues were erected in the public places of Rome.

This series of crimes, in spite of the unvarying applause which still greeted all Nero’s acts, had excited gloomy forebodings of coming evil, and the general uneasiness was increased by the events which followed. In 63 the partial destruction of Pompeii by an earthquake, and the news of the evacuation of Armenia by the Roman legions, seems to confirm the belief that the blessing of the gods was no longer with the emperor. A far deeper and more lasting impression was produced by the great fire in Rome, an event which more than almost any other has thrown a lurid light round Nero’s reign. The fire broke out on the night of July 18, 64, among the wooden booths at the south-east end oft the Circus Maximus. Thence in one direction it rapidly spread over the Palatine and Velia up to the low cliffs of the Esquiline, and in another it laid waste the Aventine, the Fortum Boarium, and Valabrum till it reached the Tiber and the solid barrier of the Servian wall. After burning fiercely for six days, and when its fury seemed to have exhausted itself, it suddenly started afresh in the northern quarter of the city, and desolated the two regions of the Circus Flaminius and the Via Lata. By the time that it was finally quenched only four of the fourteen regions remained untouched; three had been

utterly destroyed, and seven reduced to ruins. The conflagration is said by all authorities later than Tacitus to have been deliberately caused by Nero himself.1 But Tacitus, though he mentions rumours to that effect, declares that its origin was uncertain, and his description of Nero’s energetic conduct at the time justifies us in acquitting the emperor of so reckless a piece of incendiarism. By Nero’s orders, the open spaces in the Campus Martius were utilized to give shelter to the homeless crowds, provisions were brought up from Ostia, and the price of corn lowered. In rebuilding the city every precaution was taken against the recurrence of such a calamity. Broad regular streets replaced the narrow winding alleys. The new housed were limited in height, built partly of hard stones, and protected by open spaces and colonnades. The water supply, lastly, was carefully regulated. But there is nevertheless no doubt that this great disaster told against Nero in the popular mind. It was regarded as a direct manifestation of the wrath of the gods, even by those who did not share the current suspicions of the emperor’s guilt. This impression no religious ceremonies, nor even the execution of a number of Christians, hastily pitches upon as convenient scapegoats, could altogether dispel. Nero, however, undeterred by forebodings and rumours, proceeded with the congenial work of repairing the damage inflicted by the flames. Ina addition to the rebuilding of the streets, he gratified his love of magnificence and talked of long after its partial demolition by Vespasian. It stretched from the Palatine across the low ground, afterwards occupied by the Colosseum, to the Esquiline. Its wall blazed with gold and precious stones; masterpieces of art from Greece adorned its walls; but most marvelous of all were the grounds in which it stood, with their meadows and lakes, their shady woods, and their distant views. To defray the enormous cost, Italy and the provinces, says Tacitus, were ransacked, and in Asia and Achaia specially the rapacity of the imperial commissioners recalled the days of Mummius and of Sulla. 2 It was the first occasion on which the provincials had suffered from Nero’s rule, and the discontent it caused helped to weaken his hold over them at the very moment when the growing discontent in Rome was gathering to a head. For early in 65 Nero was panic-stricken amid his pleasures by the discovery of a formidable conspiracy against his life and rule. Such conspiracies, prompted partly by the ambition of powerful nobles and partly by their personal fears, had been of frequent occurrence in the history of the Caesars, and now Nero’s recent excesses, and his declining popularity, seemed to promise well for the success if the plot. Among the conspirators were many who held important posts, or belonged to the innermost circle of Nero’s friends, such as Faenius Rufus, Tigellinu’s colleague in the prefecture of the praetorian guards, Plautius Lateranus, one of the consuls elect, the poet Lucan, and, lastly, not a few of the tribunes and centurions of the praetorian guard itself. Their chosen leader, whom they destined to succeed Nero, was C. Calpurnius Piso, a handsome, wealthy, and popular noble, and a boon companion of Nero himself. The plan was that Nero should be murdered when he appeared as usual at the games in the circus, but the design was frustrated by the treachery of a freedom Milichus, who, tempted by the hope of a large reward, disclosed the whole plot to the emperor. In a frenzy of sudden terror Nero struck right and left among the ranks of the conspirators. Piso was put to death in his own housel and his fall was rapidly followed by the execution of Faenius Rufus, Lucan, and many of their less prominent accomplices. Even Seneca himself, though there seems to have been no evidence of his complicity could not escape the frantic suspiciousness of the emperor, stimulated as it may have been in his case by he jealousy of Tigellinus and Poppaea. The order for his death reached him in his country house near Rome, and he met his fate with dignity and courage. For the moment Nero felt safe; but, tough largesses and thanksgiving celebrated the suppression of the conspiracy, and the dazzling round of games and shows was renewed with even increased splendour, the effects of the shock were visible in the long and dreary list of victims who during the next few months were sacrificed to his restless fears and savage resentment. Conspicuous among them was Paetus Thrasea, whese irreconcilable non-conformity and unbending virtue had long made him distasteful to Nero, and who was now suspected, possibly with reason, of sympathy with the conspirators. The death of Poppaea in the autumn of 65 was probably not lamented by any one but her husband, but the general gloom was deepened by a pestilence, caused, it seems, by the overcrowding at the time of the fire, which decimated the population of the capital. Early, however, in the summer of 66, the visit of the Part of the Parthian prince Tiridates to Italy seemed to shed a ray of light over the increasing darkness if Nero’s last years. Corbulo had settled matters satisfactorily in Armenia. The Parthians were gratified by the elevation to the Armenian throne of their king’s brother, and Tiridates, in return, consented to receive his crown from the hands of the Roman emperor. In royal state he traveled to Italy, and at Rome the ceremony of investiture was performed with the utmost splendour. Delighted with this tribute to his greatness, Nero for a moment dreamt of rivaling Alexander, and winning fame as a conqueror. Expeditions were talked of to the shores of the Caspian Sea and against the remote Ethiopians, but Nero was no soldier, and he quickly turned to a more congenial field for triumph. He had long panted for as opportunity of displaying his varied artistic gifts before a worthier and more sympathetic audience than could be found in Rome, With this view he had already, in 64, appeared on the stage before the half-Greek public of Naples. But his mind was now set on challenging the applause of the Greeks themselves in the ancient home of art. Towards the end of 66 he arrived in Greece, accompanied by a motley following of soldiers, courtiers, musicians, and dancers, determined to forget for a time Rome and the irksome affairs of Rome with its conspiracies and intrigues. No episode in Nero’s reign has afforded such plentiful material for the imagination of subsequent writers as his visit to Greece; but, when every allowance is made for exaggeration and sheer invention, it must still be confessed that the spectacle presented was unique.3 The emperor appeared there professedly as merely as enthusiastic worshipper of Greek art, and a humble candidate for the suffrages of Greek judges. At each of the great festivals, which to please him were for once crowded into a single year, he entered in regular form for the various competitions, scrupulously conformed to the tradition and rules of the arena, and awaited in nervous suspense the verdict of the umpires. The dexterous Greeks, flattered by his genuine enthusiasms, humoured him to the top of his bent. Everywhere the imperial competitor was victorious. Crowns were showered upon him, and crowned audience importuned him to display his talents. The delighted emperor protested that only the Greeks were fit to hear him, and their ready complaisance was rewarded when he left by the bestowal of immunity form the land tax on the hole province, and the gift of the Roman franchise to his appreciative judges, while as a more splendid and lasting memorial of his visit, be planned and actually commenced the cutting of a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth. If we may believe report, Nero found time in the intervals of his artistic triumphs for more vicious excesses. The stories of his mock marriage with Sporus, his execution of wealthy Greeks for the sake of their money, and his wholesale plundering of the temples were evidently part of the accepted tradition about him in the time of Suetonius, and are at least credible. Far more certainly true is his ungrateful treatment of Domitius Corbulo, who, when he landed at Cenchreae, fresh from his successes in Armenia, was met by an order for his instant execution and at once put an end to his own life.

But while Nero was reveling in Greece the dissatisfaction with his rule, and the fear and abhorrence excited by his crimes, were rapidly taking the shape of a resolute determination to get rid of hi,. That movements in this direction were on foot in Rome may be safely inferred from the urgency with which the imperial freedman Helius insisted upon Nero’s return to Italy; but far more serious than any amount of intrigue in Rome was the disaffection which showed itself in the rich and warlike provinces of the wets. In northern Gaul, early in 68, the standard of revolt was raised by Julius Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunesis, and himself the head of an ancient and noble Celtic family. South of the Pyrenees, P. Sulpicius Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, and Poppaea’s former husbandm Marcus Salvius Otho, governor of Lusitania followed Vindex’s example. At first, however, fortune semed to favour Nero. It is very probable that Vindex had other aims in view than the deposition of Nero and the substitution of a fresh emperor in his place, and that the liberation of northern Gaul from Roman rule was part of his plan. 1 If this was so, it is easy to understand both the enthusiasm with which the chiefs of northern Gaul rallied to the standard of a leader belonging to their own race, and the opposition which Vindex encountered form the Roman colony of Lugdunum, and form the Roman legions on the Rhine. For it is certain that the latter at any rate were not animated by loyalty to Nero. They encountered Vindex and his Celtic levies at Vesontium (Besancon), and in the battle which followed Vindex was legionaries was to break the statues if Nero and offer the imperial purple to their own commander Verginius Rufus; and the latter, though he declined their offer appealed to them to declare for the senate and people of Rome. Meanwhile in Spain Galba had been saluted imperator by his legions, had accepted the title, and was already on his march towards Italy. On the road the news met him that Vindex had been crushed by the army of the Rhine, and despair, and even thought of suicide. Had Nero acted with energy he might still have checked the revolt. But he did nothing, He had reluctantly left Greece early in 68, but retuned to Italy only to renew his revels. When on March 19 the news reached hum at Naples of the rising in Gaul, he allowed a week to elapse before he could tear himself away form his pleasures. When he did at last re-enter Rome, he contented himself with the empty form of proscribing Vindex, and setting a price on his head. In April the announcement that Spain also had revolted, and that the legions in Germany had declared for a republic, terrified him to something like energy. But it was too late. The news form the provinces fanned into flame the smouldering disaffection in Rome. During the next few weeks the senate almost openly intrigued against him, and the populace, once so lavish of their applause, were silent of hostile. Every day brought fresh instances of desertion, and the fidelity of the praetorian sentinels was more than doubtful. When finally even the palace guards forsook their posts, Nero despairingly stole out of Rome to seek shelter in a freedman’s villa some four miles off. In this hiding-place he heard of the senate’s proclamation of Galba as emperor, and of the sentence of death passed on himself. On the approach of the horsemen sent to drag him to execution, he collected sufficient courage to save himself by suicide form this final ignominy, and the soldiers arrived only to find the emperor in the agonies of death. Nero died on June 9, 68, in the thirty-first year of his age and the fourteenth of his reign, and his remains were deposited by the faithful hands of acte in the family tomb of the Domitii on the Pincian Hill. With his death ended the line of the Caesars, and Roman imperialism entered upon a new phase. His statues were broken, his name everywhere erased, and his golden house demolished; yet, in spite of all, no Roman emperor has left a deeper mark upon subsequent tradition. His brief career, with its splendid opening and its tragic close, its fantastic revels and frightful disasters, acquired a firm hold over the imagination of succeeding generations. The Roman populace continued for a long time to reverence his memory as that of an open-handed patron, and in Greece the recollections of his magnificence, and his enthusiasm for art, were still fresh when the traveler Pausanias visited the country a century later. The belief that he had not really died, but would return again to confound his foes, was long prevalent, not only in the remoter provinces, but even in Rome itself; and more than one pretender was able to collect a following by assuming the name of the last of the race of Augustus. More lasting still in its effects was the implacable hatred cherished towards his memory by those who had suffered from his cruelties. Roman literature, faithfully reflecting the sentiments of the aristocratic salons of the capital, while it almost canonized those who had been his victims, fully avenged their wrongs by painting Nero as a monster of wickedness. In Christian tradition he appears in an even more terrible character, as the mystic Antichrist, who was destined to come once again to trouble the saints. Even in the Middle Ages, Nero is still the very incarnation of splendid iniquity, while the belief lingered obstinately that he had only disappeared for a time, and as late as the 11th century his restless spirit was supposed to haunt the slopes of the Pincian Hill.

The chief ancient authorities for Nero’ life and reign are Tacitus (Annals, xiii.-xvi.), Suetonius, Dio Cassius (Epit., lxi., lxii., lxiii.), and Zonaras (Ann., xi). The most important modern works are Merivale’s History of the Romans under the empire; H. Schiller’s Nero, and his Geschichte d. Kaiserzeit; Lehmann, Claudius und Nero. (H. F. P.)

Footnotes

(348-1) Tac., Ann., xii. 26, 36; see also Schiller, Nero, 67.

(348-2) Tac., Ann., xii. 26; Zonaras, xi. 10.

(348-3) Tac., Ann., xii. 41

(348-4) Tac., Ann., xii. 96; Suet., Nero, 8.

(349-1) Tac., Ann., xiii. 12-20.

(349-2) Ibid., xic. 1-13

(349-3) Tax., Ann., xiv. 59

(350-1) Tac., Ann., xv. 38; Suet., Nero, 38; Dio Cass, lxii. 16; Pliny. N.H., vii. 5.

(350-2) Tac., Ann., xv. 42; Suet., Nero, 31; cf. Friedländer, Sittengeschichte, iii. 67-69.

(350-3) Suet, Nero, 19-24; Dio Cass., Epit., lxiii, 8-16.

(351-1) Suet., Nero, 40; Dio Cass, Epit., lxiii. 22; Plut, Galba. 4; cf. also Schiller’s Nero, pp. 261 sq.; Mommsen in Hermes, xiii. 90.

The above article was written by: Henry Francis Pelham, M.A., LL.D., F.S.A.; President of Trinity College, Oxford, from 1897; Camden Professor of Ancient History, University of Oxford, from 1889; Tutor of Exeter College, 1869-90; University Reader Ancient History, 1887; Curator of Bodleian Library, 1892; author of Outlines of Roman History, The Imperial Domains and the Colonate, The Roman Frontier System.

|